Tasting eternity

A caprine lesson in repose

By the time I reached Dharamshala, a small town in northern India that clings to the steep foothills of the Himalayas, I was frustrated and exhausted and homesick. I had spent a long day in a hot car to reach this beautiful, holy site in the mountains — but all I really wanted were the comforts of my familiar life, my old friends, and my own bed.

That first evening I wandered the valley on foot, crisscrossing between villages to get my bearings. I was huffing and stewing. After three months in India, yet another week in an unfamiliar place — my last one before flying home — yawned ahead of me. I kept asking myself: what am I doing here? On some level, I was hoping for a sign, some solace that I was meant to be there, fulfilling a larger purpose.

It was then, as I was stomping around a gorgeous Himalayan hillside like a petulant child, that I turned a corner and saw, perched on a rock jutting out into the ravine below, a goat. His snowy curls flopped down over his eyes like a moody teenager’s bangs, and long downy tresses fell from his back. He turned and looked up at me, chewing some foliage nonchalantly.

I laughed, and then I bristled. This was not exactly the sign I had in mind.

The encounter seemed an obvious envoy from god, a not-so-subtle reminder of the qualities I share with the tenacious mountain goat. (I’m a double-Capricorn, after all, embodied by the mystical sea-goat hybrid.) I was annoyed at the nudge. I wasn’t feeling remotely goaty. I didn’t want to be persistent or independent. I wanted softness, familiarity, ease. But it seemed the circumstances — alone in a distant land, eight thousand miles from home — were calling for toughness.

With their boxy bodies, spindly legs, and small hooves, you wouldn’t expect a goat to ascend the craggy cliffs that it does. Its spooky, horizontal pupils expand its peripheral vision to almost 360 degrees, affording it uncanny awareness and balance. Bluffs that look unclimbable to us are cakewalks to a goat, who navigates mostly by intuition. A goat doesn’t doubt its own toughness or throw a tantrum when it would rather sit around eating grass than climb. It just eats when it’s hungry, rests when it’s tired, and carries on.

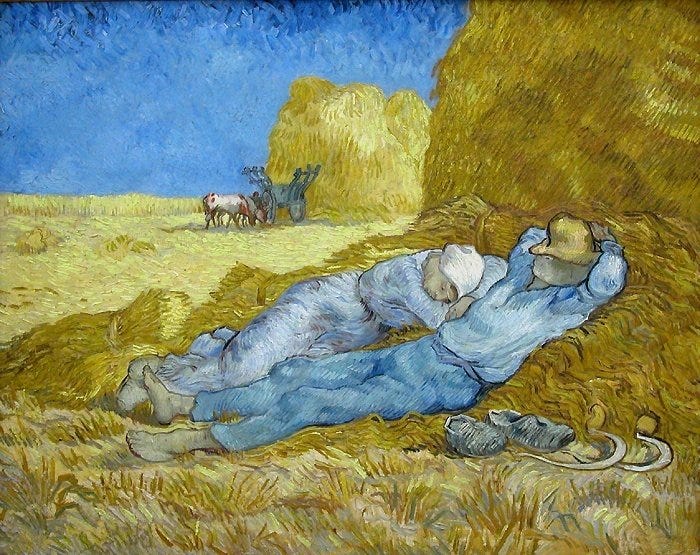

At the time, I thought I understood the message: keep climbing. Be steadfast, resilient, self-reliant. That interpretation fit comfortably with the way I had always lived. But only later did I realize that when I met the goat, it wasn’t climbing at all. It was paused — composed, aware, entirely unhurried. It had stopped not because it was lazy or lost but because the pause itself was part of its movement.

I’ve spent most of my life identifying with the goat’s drive rather than its rest. I’m wired to climb, to seek, to improve. I’m allergic to inertia; the mere whiff of stasis sends me into a tailspin. In some ways that impulse has served me well — it’s given me purpose, accomplishment, stimulation. But unbalanced by stillness, it leaves me depleted. It turns out I need both: a place to sit and chew on grass, and soon enough, another mountain to climb.

For the past six months, I have looked toward November as a moment of pause. I had projects and events stacked up one after another from June through October, and I promised myself that once daylight savings hit, there would be a shift. I had been putting all my energy into other people’s ventures — something I love to do, and am good at, and if I’m not careful, something I’ll say yes to again and again until the end of time, when I realize years have passed and I haven’t made anything of my own. So I turned down winter opportunities, and when people asked, “what projects?” I’d have to say, I don’t know yet. I wouldn’t know what would fill the space until I made it.

Now here it is, November at last, and I feel — honestly — a bit lost. In my imagined version of this time, there was no pause between the space-making and the space-filling. I expected that the moment I said no to someone else, inspiration would arrive like a thunderbolt. But instead, I’m floating in an abyss. I walk the dog, roast squash, check trivial chores off my list. I putter. My basement is so, so organized.

Every day I wonder: is this the day I’ll have my stroke of genius? I sit on the couch by the fire, trying to empty my mind and wait for my next great idea to wander in through the front door or slip down the flue like a little miracle. Obviously, it’s too much pressure. So far I am wanting for revelations — and I can’t even enjoy the spaciousness I so desperately sought and so carefully created for myself.

What surprises me most is the shame. I have this thing that I dreamed of — that so many people yearn for — and I can’t bring myself to enjoy it. I feel embarrassed that it’s possible for me, as if time itself were a guilty pleasure. Our culture trains us to believe that rest is idleness, and idleness is waste. Even when I know better, I can feel that belief in my body: the guilt that rises when the calendar is blank, the twitch to fill it.

But maybe the problem is that I still think of rest as not-doing rather than an activity all its own. In the Jewish tradition, the Sabbath exists precisely to teach and protect the act of rest. An ancient practice, it guards a realm where sacredness resides not in productivity but in presence. In The Sabbath: Its Meaning for Modern Man, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel described the Sabbath as a time to “care for the seed of eternity planted in the soul.” The purest holiness, he wrote, is found not in space — which humans can mold and dominate — but in time, which resists our control. “The likeness of God can be found in time,” he said, “which is eternity in disguise.”

Not only that, but Heschel saw the Sabbath as an important opportunity to sample the true rest that would be offered to us permanently in the afterlife. He suggested that we practice pure presence in this life, so that once we get to heaven — or nirvana, the promised land, the cosmos… — we’ll be well prepared to behave accordingly. “Unless one learns how to relish the taste of Sabbath,” he cautioned, “one will be unable to enjoy the taste of eternity in the world to come.”

Heschel’s vision of Sabbath has nothing to do with idleness. “Labor is a craft,” he wrote, “but perfect rest is an art.” This idea feels radical. We treat stillness like death, when in truth the practice of simple presence — through pause, contemplation, and sacred attention — roots us in our true nature. Without that rhythm, life blurs into endless conquest: more tasks, more motion, more noise. As Heschel warned, “The danger begins when in gaining power in the realm of space we forfeit all aspirations in the realm of time.”

It took a wise friend to remind me that the goat I witnessed wasn’t scampering up a mountain, but surveying its progress. That its pause wasn’t laziness; it was calibration. It knew when to move and when to rest, guided by instinct rather than anxiety. I wonder what would happen if I approached my own pauses that way — not as breaks from life but as moments inside it, opportunities to regain balance before the next ascent.

The goat’s message for me wasn’t to keep climbing, but something more encouraging: a reminder that I’d already been on a long journey, that now might be a time to step back and take stock, that soon enough I’d be ready to climb again.

The rituals marking my present uneasy Sabbath are the quiet domestic rhythms of early winter: a dog curled by a fire, long evenings, a shock of red in a Japanese maple. I keep waiting for clarity about what should fill this time, but of course clarity is not the point. The point is to inhabit unfilled time without fear, to learn to savor the taste of eternity. And then, when the time comes, to carry on up the mountain.

Thanks Ellie

The reframing of the goat encounter is beutiful. I find myself in a similar place, always thinking rest needs to be earned through productivity. Your point about Heschel's view of Sabbath as an art rather than idlenes really struck me. It's counterintuitive to see pause as calibration instead of wastd time, but I think that's exactly what I need to hear right now.